So you’ve been playing around with XNA for the last few weeks/months and now want to get into the thick of things and make a game. Without too much experience in 3D programming you opt to go the 2D route, but you’d rather not make another asteroids clone or a top-down RPG. You’re idea is a fast-paced action 2D game. Sure, it’s probably nothing too innovative, but it hasn’t been done too often that it’d get overlooked immediately.

This article is aimed for those looking for ideas on how to implement vibrant, art-heavy 2D worlds without sacrificing too much of their ‘original vision’ and allowing their artist much more freedom in terms of expression and less constraints from the actual game implementation. We’ll first look at some of the bumps in the road that we have to overcome in order to get our game complete and running smoothly. Here’s a list of the initial things one will come up against

- Graphics cards, for the most part, like 3D more than 2D.

- We only have so much memory, on both the video card and system RAM. This’ll probably be your biggest hurdle to overcome.

- Making your 2D rendering framework flexible enough to let the artist have more artistic freedom, but still feasible that it can run on most systems.

Let’s face it, games are going the way of 3D. With that said, why not use some of the raw processing power the new 3D graphics cards are tapping into and use it for our 2D games? I haven’t really seen a 2D game that fully embraced modern hardware on the PC. Well that’s not entirely true. Plasma Pong is a nice preview of what you can do with 3D hardware in a 2D environment. I’m sure more innovative ways to use 3D hardware in 2D will be coming over the next few years.

The other limitation is memory. 3D has an advantage because it can use the same tiny texture and apply it to numerous models and make them appear different simply by their orientation or distance from the camera. It’s a nice example of data compression. With 2D, if you used the same texture everywhere your game would look bland! We have to come up with better ways of data compression and manipulation in 2D. And this is what we’ll be exploring in this article.

Making a flexible 2D rendering framework is probably beyond the scope of this article, but I’ll touch on some things like optimizations for rendering that may help gain a few frames a second. Now I’ll go into some of the ideas and tips I have for beginners looking to make an art heavy 2D game.

If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it

My first advice is to go ahead and do what you think would work. Best way to find out the limitations of hardware and software is to play with your own ideas. Sometimes you can simply brute force render 2D worlds with little optimization simply because todays computers can handle it with minimal slow down. If you’re game can do this on a wide range of computers already then you’re time could probably be best spent elsewhere so you’re game gets done! Shoot for perfection, but don’t be dissappointed when you’re not quiet there!

Tiling

This’ll probably be the first thing you’ll look into when trying to create large scrolling 2D environments. And most likely, when you look up information on creating a 2D tiling engine you’ll be met with countless ‘how to make a top-down 2D RPG tiling engine’ tutorial. Don’t be deterred though, as much of the advice and knowledge you can gain from reading those tutorials are very applicable to making a fast-scrolling multi-layered 2D scroller. It just might not be what you are looking for in terms of style of game :). This is where your creativity comes in! Many of the top-down role-playing games you see as examples use tile sets to create the illusion of huge worlds. They make repeatable tiles that can be re-used over and over again with wreckless abandon. As a result, you are left with a limited way of creating elaborate 2D landscapes and environments. Now, I’ll go over those techniques that were used in developing Gunstyle and are being used to develop WildBoarders in XNA. Both games are fast-paced side scrollers. Gunstyle was developed as a complete multiplayer game, and Wildboarders as more of a learning experience in getting acquainted with XNA.

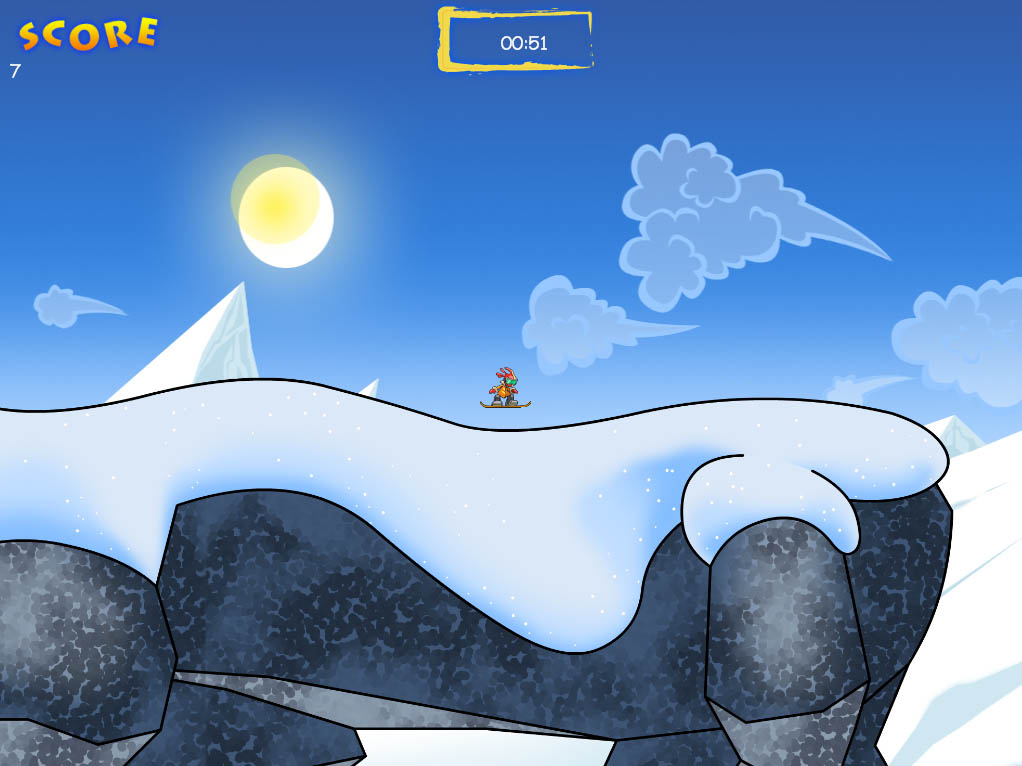

First off, what do you initially notice in these two pictures below?

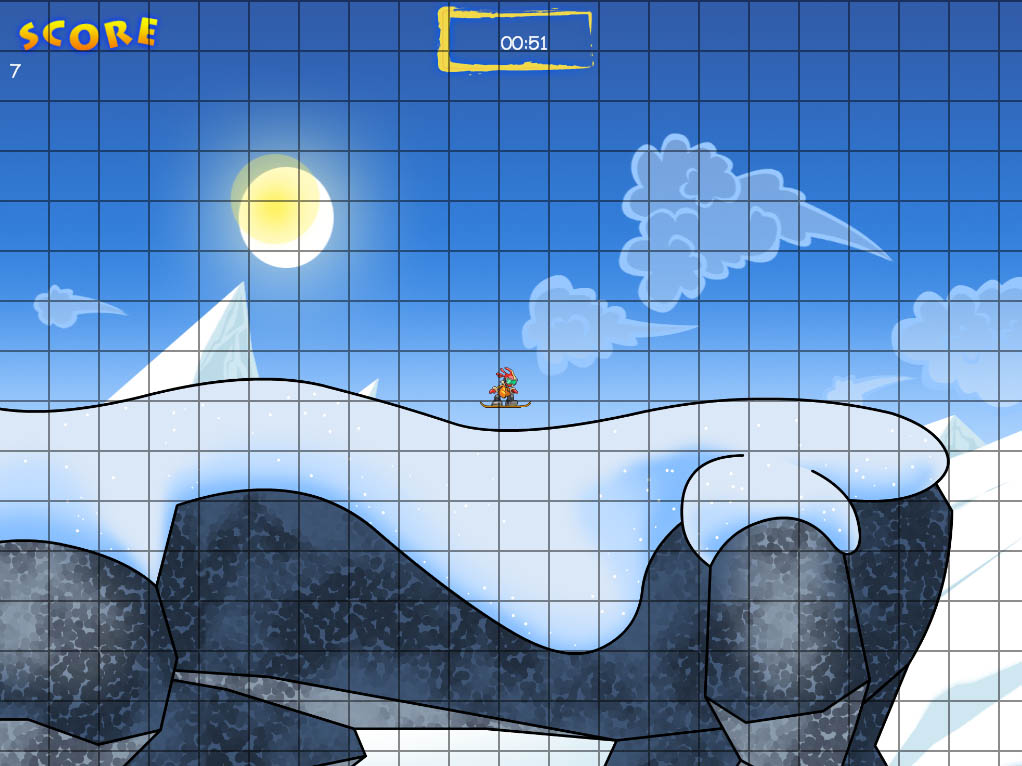

You might have noticed that there doesn’t appear to be any sort of obvious tiling in either of the images, and that they might just be large scrolling pictures. Well the truth is, they both use tiling extensively. Below is an image of the approximate slicing of the tiles in WildBoarders.

At the time of this writing WildBoarders is using more of a ‘brute force’ approach to it’s tile rendering. There are some slight optimizations, but in the end the game isn’t doing anything too complex and the need for optimization isn’t as great as opposed to the far more complex Gunstyle. The code powering this tiling is rather simple in WildBoarders. In fact, the majority of it is handled by my 2D camera class. If you read and understood my simple 2D camera tutorial, then you’re well on your way to creating 2D scrollable worlds. These worlds are created by the artist on a very large, high resolution image. Then after a few tweaks, the images are shrunken, cut up, and then indexed with numbers for their position in the 2D world. So for example, tile0.png would be the far top left of the world, and tile_3453.png is probably somewhere lower and to the right of the world scene. As you could imagine, there could be _lots of unique tiles, which in turn takes a lot of memory to process and hold. Now you’ve come to the area of ‘creative’ tile management. I’ll be sharing our solution that we used for Gunstyle to achieve fast tiling with the minimal amount of memory, as WildBoarders is still in development and at the moment doesn’t do much more in terms of clipping and some dynamic loading.

Optimizations

** 1. Clipping.**

Having poor frame rates with your 2D game? This is the first thing to check. Make sure you’re not drawing anything you don’t have to! The fact that you’re dealing with simple rectangles should make it many times easier than dealing with 3D scenes. Doing a simple rectangle overlap check with your screen and the tile in question is usually sufficient.

** 2. Hard drive loading**

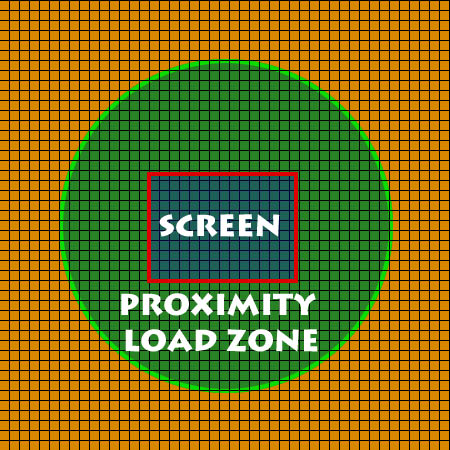

Still not saving enough memory? If you’re game isn’t too fast then you could attempt to have some sort of perimeter zone around your screen that keeps these tiles loaded, while tiles outside this zone are freed from memory. Once a tile enters this ‘perimeter’ zone then you can load the tile. This zone should probably be bigger than your screen so you’re not loading things just as they are needed. Another trick is to limit the amount of tiles that can be loaded per frame. If you tried this without it you might find your FPS dipping to undesirable rates (especially on slower hard drives). You can consider the outer zone as a ‘get ready to load’ zone. For example, you could limit it to loading only 10 tiles per frame. So in a second you’ve loaded 60 tiles (at 60 fps) into memory and potentially freed 60 tiles from memory. This’ll make it much more feasible to make expansive worlds without worrying too much about memory requirements. Hopefully the illustration below will clear things up a bit more.

The grid represents your tiles in your world and the green circle represents all the tiles surrounding your view of the world (the screen) that should be loaded. Limit the loading to some set number per frame and it’ll help ease off the hit of loading and unloading assets into memory. This should solve most games memory issues, but it didn’t completely solve ours with Gunstyle.

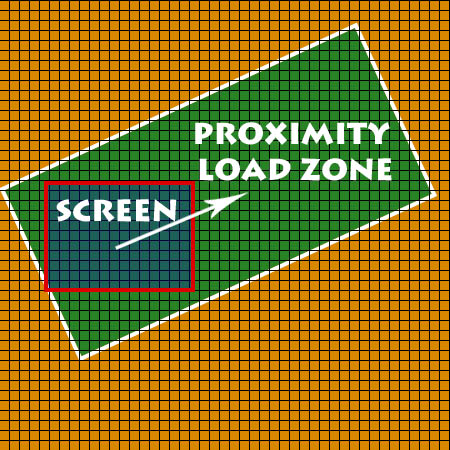

** 3. Advanced Hard drive loading**

Gunstyle had a very open physics system that allowed players to reach speeds across maps that where pretty insane. Experienced players could go across a map in little under 3-4 seconds on some of the largest maps. This posed a problem for us when trying to manage all the tile that were quickly entering and leaving the player’s field of view. So our solution was to take the hard drive loading a step further. We essentially load tiles based off the direction the player is moving towards and let tiles ‘time out’ from memory. Essentially, as the player moves back and forth on a map there’ll be more of a favorable path the player will have a bias too. When the player’s trajectory encounters a new tile that hasn’t been loaded, it’ll load it. Once that tile leaves the player’s trajectory it does not unload from memory, but starts counting down. After a set time, if the player hasn’t returned to this area that tile will be freed from memory. There’s several advantages to this technique. First off, if the player never visits that remote corner of the map during this sessions, then they won’t ever load that portion into memory! Secondly, this reduced the hit of loading things into memory quiet a bit. For example, as the player moved to the right we could ignore the tiles above and below him as he travelled since we assumed he is not likely to suddenly go upwards by a great degree. Of course, players are pretty unpredictable so we had fail safes for such instances. If a tile every did get into the view port of the player it’d be forced to load. We also made sure not to load too many tiles each frame. Overall, this system provided a nice scalable solution to drawing large 2D worlds. Below is a simple illustration of how the system worked.

As the player’s speed increased so did the box’s width (setting a limit eventually). When the player’s speed was zero the box was simply centered around the player’s screen. This provided us with enough savings on memory to allow most computers to play Gunstyle.

Conclusion and other thoughts

Well I hope this article’s been useful. Most would probably know about tiling images to create a bigger image, but hopefully I could have spurred some ideas on how to dynamically load tiles efficiently and achieve the needed performance for fast-paced 2D action games ;)! Some other topics that I’m interested in and will be looking into for future 2D games are procedural textures, and mix-and-match asset combinations to create different images, so stay tuned! ~